CAES Student Partnership Initiative

Dr Lisa Cheung, Centre for Applied English Studies, Faculty of Arts, HKU

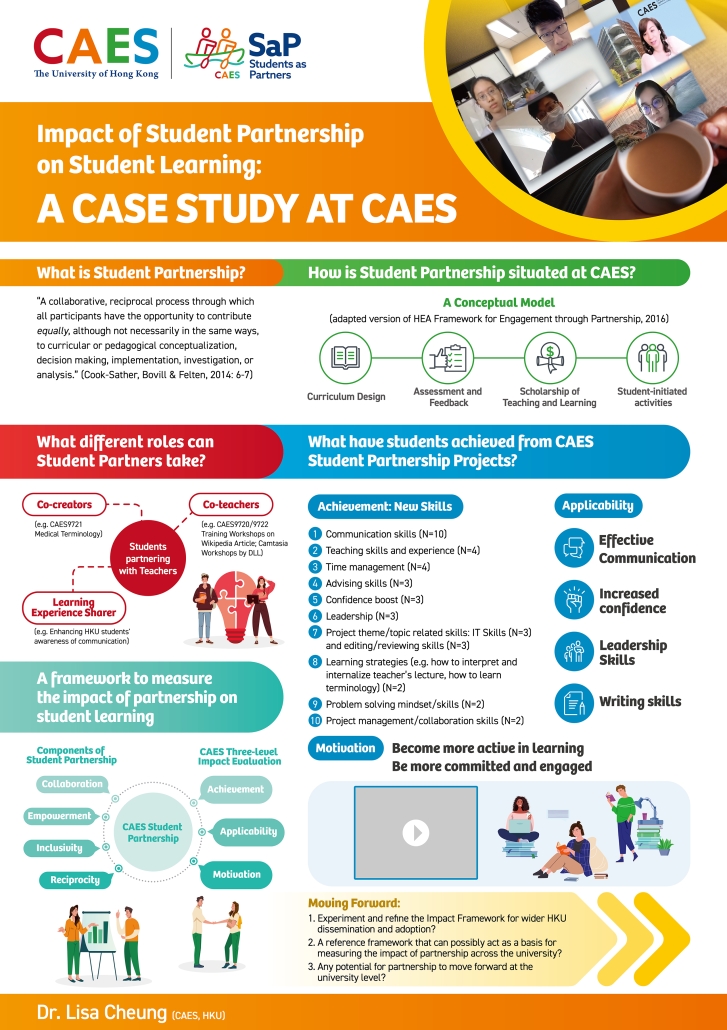

A total of five projects were organized under the Students as Partners (SaP) initiative at CAES in the 2020-22 academic year. There were three course-related projects (Medical Terminology project arising from the CAES9721 course, Wikipedia Article project from the CAES9720 and CAES9722 courses, Nurturing Global Leaders programme NGL) and two project- or service- related ones (the Communication-Intensive Course project and the Digital Literacy Lab under the CAES Communication Support Services).

Five outcomes achieved from successful collaboration were reported: Camtasia Workshops (DLL), Medical terminology course materials and activities, Wikipedia Article technical assistance, brand-new publication that highlights the NGL experiential learning experiences: Paper Plan – a#MYstory Collection, and poster/video for the Communication-intensive Course (CiC) project.

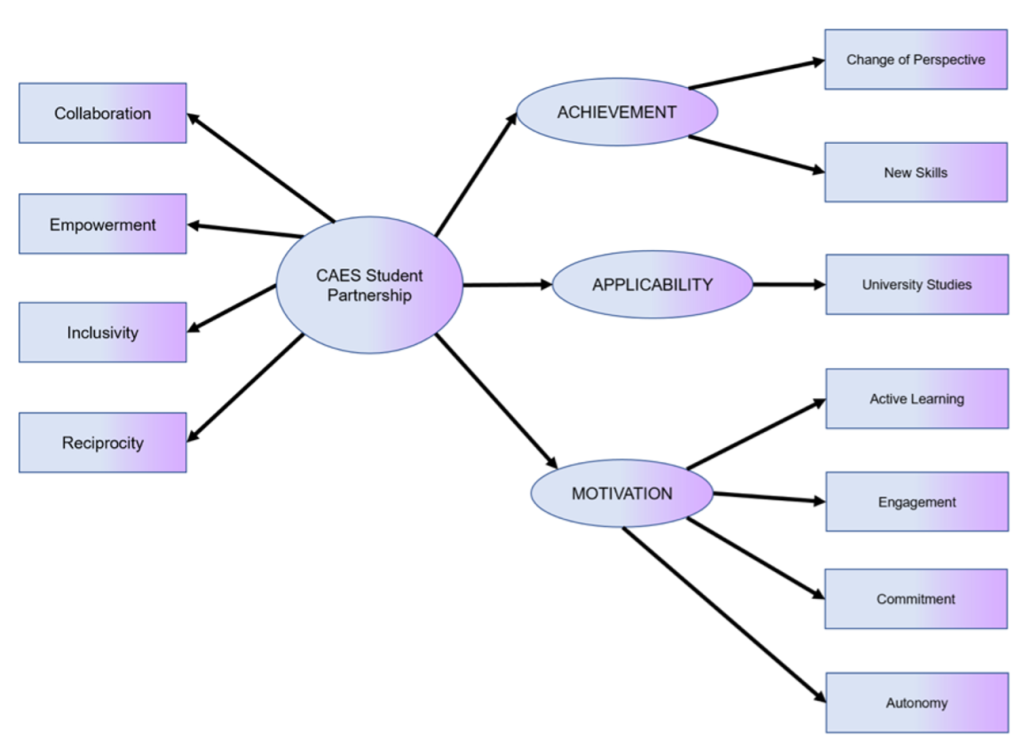

An impact framework was developed to measure the impact of CAES student partnership on student learning (see Figure 1). Six core values of SaP identified in the literature, including Autonomy, Commitment, Inclusivity, Partnership (or Collaboration), Empowerment, and Reciprocity, were incorporated into the framework to evaluate the benefits of SaP on student learning.

The components of student partnership are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Tables 1 - Components of CAES Student Partnership

| Input | Definition |

|---|---|

| Collaboration | Student partnership is a collaborative process through which all participants have the opportunity to contribute equally (Cook-Sather, Bovill & Felten, 2014). Effective partnership is respectful, mutually beneficial learning where students and staff work collaboratively on all aspects of educational endeavours. |

| Empowerment | Students are ‘expert’s on being students. This expert understanding of the student experience is just as important and valuable as teachers’ disciplinary expertise (Mihans, Long & Felten, 2008). Thus, partnership allows space for shared power, and through such relationship students and staff bring different expertise to the collaboration. When staff begin to share responsibility with students, both staff and students create an environment where respect and trust is developed. During such trust building process, staff members are open and receptive to feedback, and a shift of power can be seen from hierarchical to equal in the process of collaboration. |

| Inclusivity | Moore-Cherry, Healey, Nicholson and Andrew (2016: 84) proposed the term inclusive partnership to conceptualise a non-selective staff-student relationship that “facilitates better and more meaningful engagement of all students through empowerment and confidence building”. It is suggested that the diversity of learning spaces provide opportunities for engaging students to the broader community of scholarly education (Moore-Cherry et al, 2016). Effective partnership allows a party involved in a collaborative relationship to feel like who he/she is more than enough, and that his/her identity, thoughts, and ideas are significant and valuable. |

| Reciprocity | Reciprocity is reflected in the “act of students sharing their experiences and staff members contributing their expert knowledge” (Martens, et al, 2019: 911). What is important about this value is that partnerships are mutualistic and benefit all parties involved who are working together for good. |

Tables 2 - CAES three-level impact evaluation model for measuring student partnership

| Construct | Subconstruct | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 Achievement | Change of perspective New skills | The extent to which students are provided with an insight into the complex world of higher education to question the adequacy of a passive role in their learning, and the extent of students’ learning gains in knowledge and skills through partnership (e.g. being reflective, team working, increased confidence and so forth). |

| Level 2 Applicability | University studies | Students’ recognition and application of the change of perspective and learnt skills from current contexts to new (e.g. learning strategies in other academic courses) contents. |

| Level 3 Motivation | Active learning Engagement Commitment Autonomy | The extent to which students are motivated by the partnership to become more active in learning, enhance engagement, develop a sense of commitment, and enhance autonomy. |

Tables 1 – Components of CAES Student Partnership

- Input

- Collaboration

- Empowerment

- Inclusivity

- Reciprocity

- Definition

- Student partnership is a collaborative process through which all participants have the opportunity to contribute equally (Cook-Sather, Bovill & Felten, 2014). Effective partnership is respectful, mutually beneficial learning where students and staff work collaboratively on all aspects of educational endeavours.

- Students are ‘expert’s on being students. This expert understanding of the student experience is just as important and valuable as teachers’ disciplinary expertise (Mihans, Long & Felten, 2008). Thus, partnership allows space for shared power, and through such relationship students and staff bring different expertise to the collaboration. When staff begin to share responsibility with students, both staff and students create an environment where respect and trust is developed. During such trust building process, staff members are open and receptive to feedback, and a shift of power can be seen from hierarchical to equal in the process of collaboration.

- Moore-Cherry, Healey, Nicholson and Andrew (2016: 84) proposed the term inclusive partnership to conceptualise a non-selective staff-student relationship that “facilitates better and more meaningful engagement of all students through empowerment and confidence building”. It is suggested that the diversity of learning spaces provide opportunities for engaging students to the broader community of scholarly education (Moore-Cherry et al, 2016). Effective partnership allows a party involved in a collaborative relationship to feel like who he/she is more than enough, and that his/her identity, thoughts, and ideas are significant and valuable.

- Reciprocity is reflected in the “act of students sharing their experiences and staff members contributing their expert knowledge” (Martens, et al, 2019: 911). What is important about this value is that partnerships are mutualistic and benefit all parties involved who are working together for good.

| Input | Definition |

|---|---|

| Collaboration | Student partnership is a collaborative process through which all participants have the opportunity to contribute equally (Cook-Sather, Bovill & Felten, 2014). Effective partnership is respectful, mutually beneficial learning where students and staff work collaboratively on all aspects of educational endeavours. |

| Empowerment | Students are ‘expert’s on being students. This expert understanding of the student experience is just as important and valuable as teachers’ disciplinary expertise (Mihans, Long & Felten, 2008). Thus, partnership allows space for shared power, and through such relationship students and staff bring different expertise to the collaboration. When staff begin to share responsibility with students, both staff and students create an environment where respect and trust is developed. During such trust building process, staff members are open and receptive to feedback, and a shift of power can be seen from hierarchical to equal in the process of collaboration. |

| Inclusivity | Moore-Cherry, Healey, Nicholson and Andrew (2016: 84) proposed the term inclusive partnership to conceptualise a non-selective staff-student relationship that “facilitates better and more meaningful engagement of all students through empowerment and confidence building”. It is suggested that the diversity of learning spaces provide opportunities for engaging students to the broader community of scholarly education (Moore-Cherry et al, 2016). Effective partnership allows a party involved in a collaborative relationship to feel like who he/she is more than enough, and that his/her identity, thoughts, and ideas are significant and valuable. |

| Reciprocity | Reciprocity is reflected in the “act of students sharing their experiences and staff members contributing their expert knowledge” (Martens, et al, 2019: 911). What is important about this value is that partnerships are mutualistic and benefit all parties involved who are working together for good. |

Tables 2 – CAES three-level impact evaluation model for measuring student partnership

| Construct | Subconstruct | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 Achievement | Change of perspective New skills | The extent to which students are provided with an insight into the complex world of higher education to question the adequacy of a passive role in their learning, and the extent of students’ learning gains in knowledge and skills through partnership (e.g. being reflective, team working, increased confidence and so forth). |

| Level 2 Applicability | University studies | Students’ recognition and application of the change of perspective and learnt skills from current contexts to new (e.g. learning strategies in other academic courses) contents. |

| Level 3 Motivation | Active learning Engagement Commitment Autonomy | The extent to which students are motivated by the partnership to become more active in learning, enhance engagement, develop a sense of commitment, and enhance autonomy. |

More information about CAES SaP initiative can be found on: https://caes.hku.hk/sap/

What is your working definition of Students as Partners (SaP)?

What metaphor would you use to describe the relationship with your student partners?

What obstacles to partnership did you encounter? How did you overcome it?

Lisa: One major obstacle is to enhance Teacher and Student Motivation.

We have found that recognition and reward can be extremely powerful ways of motivating students to engage in student partnership. Students can be recognized in the form of either a monetary reward (e.g. paid as Casual Helpers at HKU) or a transfer of academic credits (through the HKU Horizons Office program). At the same time, students can be encouraged to co-present or co-write with teachers on effective SaP practices, which can then be disseminated through student learning conferences or festivals at university level.

On the other hand, it is also important to encourage both extrinsic and intrinsic motivation for teaching staff to engage in SaP. These efforts had encouraged colleagues to see the need to change the status: 1) Seek to use their SaP practices as evidence for professional development. (e.g. application for the HEA fellowship); 2) Utilize their prior or existing SaP experiences to mentor less experienced or junior colleagues in practicing SaP.

What lessons did you learn or what benefits did you see from engaging in student-staff partnerships?

Lisa: The success and the lessons learnt from the SaP initiative would be extremely useful for a wider University community.

There is a need to promote a SaP ethos for colleagues through: 1) relating internal professional development themes to SaP, and 2) Recognizing SaP efforts by giving hours to colleagues who participate or lead a SaP project.

There is also a need to disseminate effective SaP approaches to a wider University community through: 1) Giving external seminars to share the impact of student partnership work with HKU colleagues; 2) Inviting scholars or visiting professors with experience of or a proven track record of effective SaP approaches from other institutions to share their practices with colleagues; 3) embedding SaP into Centre-wide or University-wide strategy documents.

What did your students gain from the student-staff partnership?

Lisa: The following shows a list of new skills that student partners have developed or improved in the partnership projects:

- Communication skills

- Teaching skills and experience

- Time management

- Advising skills

- Confidence boost

- Leadership

- Project theme/topic related skills: IT Skills and editing/reviewing skills

- Learning strategies (e.g. how to interpret and internalize teacher’s lecture, how to learn terminology)

- Problem solving mindset/skills

- Project management/collaboration skills

Regarding applicability, all student partners believed that the skills learnt in this partnership experience can be applicable to other courses or future workplace. The experience in participating and running the projects is also regarded as valuable in leading, managing and collaborating in future projects or group work by four student partners.

Considering motivation, a significant number of student partners have observed willingness to use a critical approach to information and problems that they encounter in their learning. A majority of student partners agreed that they have taken on their shared responsibility in the project, which is a core value of engagement under motivation. It is also promising to see all student partners appreciated the autonomy given throughout the collaborative process , in deciding some aspects of the project while some enjoyed freedom to take initiatives.

What takeaway message do you have for teachers who want to try out student-staff partnerships?

Lisa: Since a promising collaboration can significantly contribute to improvement of education and successful student learning, it is important to acknowledge the complexity of factors that would shape success and examine the student perceptions of partnering with teachers.

It is important to carefully plan a SaP project to draw upon the new skills that student can possibly gain (or the skills that students can possibly transfer to other courses at HKU) from such partnership experience.

What is your working definition of Students as Partners (SaP)?

What metaphor would you use to describe the relationship with your student partners?

What obstacles to partnership did you encounter? How did you overcome it?

We have found that recognition and reward can be extremely powerful ways of motivating students to engage in student partnership. Students can be recognized in the form of either a monetary reward (e.g. paid as Casual Helpers at HKU) or a transfer of academic credits (through the HKU Horizons Office program). At the same time, students can be encouraged to co-present or co-write with teachers on effective SaP practices, which can then be disseminated through student learning conferences or festivals at university level.

On the other hand, it is also important to encourage both extrinsic and intrinsic motivation for teaching staff to engage in SaP. These efforts had encouraged colleagues to see the need to change the status: 1) Seek to use their SaP practices as evidence for professional development. (e.g. application for the HEA fellowship); 2) Utilize their prior or existing SaP experiences to mentor less experienced or junior colleagues in practicing SaP.

What lessons did you learn or what benefits did you see from engaging in student-staff partnerships?

The success and the lessons learnt from the SaP initiative would be extremely useful for a wider University community.

There is a need to promote a SaP ethos for colleagues through: 1) relating internal professional development themes to SaP, and 2) Recognizing SaP efforts by giving hours to colleagues who participate or lead a SaP project.

There is also a need to disseminate effective SaP approaches to a wider University community through: 1) Giving external seminars to share the impact of student partnership work with HKU colleagues; 2) Inviting scholars or visiting professors with experience of or a proven track record of effective SaP approaches from other institutions to share their practices with colleagues; 3) embedding SaP into Centre-wide or University-wide strategy documents.

What lessons did you learn or what benefits did you see from engaging in student-staff partnerships?

The following shows a list of new skills that student partners have developed or improved in the partnership projects:

- Communication skills

- Teaching skills and experience

- Time management

- Advising skills

- Confidence boost

- Leadership

- Project theme/topic related skills: IT Skills and editing/reviewing skills

- Learning strategies (e.g. how to interpret and internalize teacher’s lecture, how to learn terminology)

- Problem solving mindset/skills

- Project management/collaboration skills

Regarding applicability, all student partners believed that the skills learnt in this partnership experience can be applicable to other courses or future workplace. The experience in participating and running the projects is also regarded as valuable in leading, managing and collaborating in future projects or group work by four student partners.

Considering motivation, a significant number of student partners have observed willingness to use a critical approach to information and problems that they encounter in their learning. A majority of student partners agreed that they have taken on their shared responsibility in the project, which is a core value of engagement under motivation. It is also promising to see all student partners appreciated the autonomy given throughout the collaborative process , in deciding some aspects of the project while some enjoyed freedom to take initiatives.

What takeaway message do you have for teachers who want to try out student-staff partnerships?

Since a promising collaboration can significantly contribute to improvement of education and successful student learning, it is important to acknowledge the complexity of factors that would shape success and examine the student perceptions of partnering with teachers.

It is important to carefully plan a SaP project to draw upon the new skills that student can possibly gain (or the skills that students can possibly transfer to other courses at HKU) from such partnership experience.